Photo credit Liz Ketcham

Gymnastics is arguably one of the world’s most difficult sports. It presents its athletes with a range of challenges, both in training and competition. Failure is a big part of the sport that plays a vital role in developing growth and resilience. Relationships with teammates and significant others in the gym, and supportive coaching are both factors that can help gymnasts overcome failure and come back even stronger 1. Considering the everlasting challenging nature of the sport, research has shown that the gymnastics environment is one where gymnasts can thrive, develop life skills, resilience and self-confidence 1. Nevertheless, resilience is the key to long term participation and a fulfilling career.

What we will be discussing in this blog

- Psychological resilience and its importance in gymnastics

- Mental fortitude training to enhance psychological resilience

- Other coaching behaviours that enhance psychological resilience

- How you can apply the above to your own coaching

What is psychological resilience?

Psychological resilience has been defined as “the role of mental processes and behavior in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors” 2. There are two types of psychological resilience:

Robust resilience– protective quality reflected in a person maintaining their well-being and performance under pressure (for example, knowing you can’t fall on beam or you won’t qualify to beam finals and being able to deliver a mistake-free routine)3.

Rebound resilience– bounce back quality reflected in minor or temporary disruptions to a person’s well-being and performance when under pressure and the quick return to normal functioning (for example, having a significant unexpected fall and being able to maintain composure and continue the routine unaffected)3.

“To come off bars and to have a fall and then go into beam and put up a strong beam routine, I was pretty proud of myself and how I handled it […] I think on beam it fueled me to do better because I didn’t want to fall again, especially after bars”

Simone Biles, 2018 US Nationals

Why is psychological resilience important in gymnastics?

Psychological resilience has been directly linked with optimal sports performance 4,5. In a sport as complex and as highly competitive as gymnastics, psychological resilience is what separates champions from the rest. In fact, research has identified what psychological qualities Olympic champions possess that helps them face the most stressful of situations. These included: positive personality, motivation, confidence, focus, and perceived social support 2. Nevertheless, if your gymnasts do not naturally have these qualities, don’t worry! There are various methods you can use as a coach to help them learn resilient behaviours. One of these methods is based on mental fortitude training.

What is mental fortitude training?

Mental fortitude training is a program developed to enhance resilience 3. The aim of mental fortitude training is to optimize an individual’s personal qualities so that he or she is able to withstand the stressors that they encounter at any given moment. Mental fortitude training should be both proactive (robust resilience) and reactive (rebound resilience) in nature and target performers before, during, and after stressful or adverse encounters. The training focuses on three main areas:

Personal qualities

Within personal qualities, we can find personality and psychological skills. Both personality and psychological skills can underpin a range of outcomes that can help gymnasts become more resilient in training and competition. The difference between personality and psychological skills is that personality is more stable over time and difficult to manipulate, whereas psychological skills can be changed and developed according to the individual 3. There is a range of psychological skills that relate positively to resilience but in the gymnastics coaching context, we will be focusing on:

- Imagery and visualisation to direct thoughts effectively– encourage the gymnast to both see and feel the skill or routine they are about to perform, this is better known as kinesthetic imagery6. This can help them feel more in control under pressure as they have already practiced the skill mentally

- Goal setting– set realistic and achievable goals with your gymnasts as this can empower them to push through any difficulties that may come along (White & Bennie, 2015). Use short term goals to achieve skills in training, long-term goals to continue to perfect performance, and outcome goals for what the gymnast wants to achieve in competition

- Planning for expected and unexpected events– practice competition routines under pressure in training and see if any problems come up. For example, your gymnast misses a dance connection on beam, therefore dropping her composition requirement by 0.5. What do you do? You inform the gymnast that this could happen in competition and in that case, they should add another two jumps to the routine to regain the requirement. This can help the gymnast feel more confident that they can correct their mistakes even when they occur mid-routine

Facilitative environment

A facilitative environment is the second area of mental fortitude training and is any setting or context that fosters the development of psychological resilience3. The two main factors to consider within the environment are those of challenge and support. Challenge involves expecting people to do their best and encouraging them to be held accountable for their success. Support involves developing peoples’ personal qualities and allowing for trust to be built alongside of learning. According to Sanford’s theory of challenge and support7 there are four different types of environments that occur as a result of differing levels of challenge and support. These are outlined below:

- Stagnant environment– Low challenge, low support. Characteristics include unstimulated participants and a culture of mediocrity.

- Comfortable environment– Low challenge, high support. Characteristics include complacency and an over-caring people where people predominantly work in their comfort zone

- Unrelenting environment– High challenge, low support. Characteristics include little care for well-being and a sink or swim mindset that often leads to burnout

- Facilitative environment– High challenge, high support. This is the type of environment coaches should strive to develop in their gyms. In this environment you can find good relationships between athletes and coaches, healthy competition and an ability to learn from mistakes and failure.

As you have observed above, a facilitative environment combines high challenge with high support. Here are some tips to make your coaching environment more facilitative:

- Feedback is important. In order to challenge your gymnasts and help them improve, provide developmental feedback. Things like “stay focused, visualise the skill before you go”. In order to make your gymnasts feel supported, provide motivational feedback. Things like “good job on reaching the goal we set, you overcame a lot of challenges in the process!”

- Have high expectations. Let your gymnasts know what you think they could potentially achieve if they work hard. Keep challenging them and pushing them to improve consistently, even in the face of setbacks.

- Encourage accountability. Let your gymnasts know that you are there to support them fully as a coach, but ultimately you can’t do the work for them and the effort they put in is what will lead to success and resilience.

Pressure Inurement Training

In our sport, gymnasts have a range of stressors in both the training and competition environments. The high difficulty of skills and fear of injury are only some of the stressors gymnasts may encounter in high pressure situations. Pressure Inurement Training (PIT) is a form of pressure manipulation in the environment that can help the gymnast learn to cope with stress under pressure. The actual definition of this type of training is the manipulation of the environment to evoke a stress-related response with the aim of maintaining functioning and performance under pressure3.

PIT can be carried out in two ways. You can either increase the demand of the stressors (e.g. having all your gymnasts sit down and watch each other’s routines whilst you judge, which is similar to a real life competition setting) or increase the significance for the appraisals (e.g. telling your gymnast that they can attempt their upgrade in a mock competition routine but if they fall they will not be allowed to compete in). PIT is a great way to see how your gymnasts cope with high pressure situations. If they are not adequately prepared and do not have enough resources to meet the demands of the manipulated training environment, they will likely react negatively. If this happens, motivational feedback and support from you as a coach can help8.On the other hand, if your gymnasts are adequately prepared and able to cope well with the pressure, you can then provide them with some more developmental feedback and challenge to allow them to continue to develop their resilience9,10.

As you can see in the figure below, it is vital to provide the right level of pressure. If too little pressure is applied, the gymnasts will not have to cope with it and therefore will not learn the appropriate facilitative responses. In contrast, if the pressure is too high, this will lead to debilitative responses that will only discourage the gymnast as they were not able to cope with the demands on the environment, therefore lowering their self-confidence11. As a coach, you know your gymnasts’ strengths and weaknesses and you should consider these when deciding how to manipulate the environment to allow your gymnasts to form resilient behaviours safely.

Challenge Mindset

The third area of mental fortitude training is one that involves a positive evaluation and interpretation of pressure encountered in combination with resources, thoughts and emotions2. The ability to change into and maintain a positive challenge mindset is the key to psychological resilience. Now that we have moved past the effect of the environment on resilience, we can start looking at how the individuals perceive stressors rather than the events which are causing stress.

When a gymnast is faced with a stressful situation, they will use appraisal to evaluate whether they have enough resources to cope with the challenge they are facing. This is commonly known as secondary appraisal12,13. Mental fortitude training can help gymnasts perceived stressful situations more positively through turning maladaptive thinking into constructive thinking3. Have you ever coached a gymnast who seemed to think negatively no matter what? Some innate personality characteristics make the perfect host for maladaptive thinking. Here are some forms of negative thinking patterns that are commonly observed:

- “End of the world” thinking– catastrophising by blowing things out of proportion and thinking that the worst has, will, or may happen. For example, a gymnast saying that they are going to have a fall at the start of the routine and have the worst routine ever as a result

- “It can’t be done” thinking– looking into the future and predicting a negative outcome. For example, a gymnast saying that they will never be able to achieve their giants, even if their coaches believe otherwise

- “It has to be perfect” thinking– viewing any mistakes as failure. For example, a gymnast who is focusing on small errors even though their overall technique is improving

This is why it is much more efficient for us as coaches to focus on changing what we are able to change, i.e. psychological skills and the environment. As a coach, it is important to highlight to gymnasts that thoughts are just thoughts and with some hard work, can be shaped and changed. Negative thoughts are likely to lead to maladaptive responses which can have detrimental effects on performance. Maladaptive thinking is something that needs to be controlled as it can lead to a cycle of rumination. Therefore, gymnasts need to be aware that they are in control of how they react to events. Negative thoughts will likely occur at some point or another, which is normal, but here are some methods to help regulate your gymnasts’ thoughts.

- Confront– encourage gymnasts to challenge their irrational thoughts. For example, if a gymnast thinks they are going to fall in competition, it is worth having you or themselves ask them “Why do you think you are going to fall if you have just done ten routines without any mistakes?”. It is much easier to rationalise thoughts when you know where they are coming from. For example, the gymnast may not actually think they are going to fall but rather is just finding it difficult to control their anxiety, which is something you can support them with.

- Replace– once the negative thoughts are identified and dealt with, they need to be replaced with positive ones. Encourage gymnasts to think about what is in their control and if there are any positives in the situation. Most situations will have at least one positive aspect to focus on but if your gymnast is really struggling to see the positive, it will likely be better for you to try to distract them from the challenge they are facing. For example, if your gymnast just had a scary fall in training and they are struggling to think positively due to the anxiety from the fall, it is worthwhile trying to simultaneously distract and support them so that they can repeat the skill safely. After this process is completed you can praise them using motivational feedback, which can help build a resilience response in the future.

Other coaching behaviours

Besides mental fortitude training, there are many other things you can do as a coach to reinforce your gymnasts’ resilience based on research1. Here are some examples:

- Ensure supportive communication– providing praise to your gymnasts and getting to know them as people as well as athletes can build a positive relationship of trust, which can make them feel more supportive and more resilient.

- Give gymnasts control– every now and then allow your gymnasts to have a say in training related decisions. This is especially useful for problem solving as it can help them become more independent and believe they are able to overcome obstacles by themselves.

- Teach skills progressively– this is probably an obvious one for a lot of you, but it can’t be emphasised enough. Provide plenty of drills and spotting when introducing gymnasts to new skills in order to make them feel more confident and more willing to face challenges that may arise.

- Show confidence in your gymnasts– as we all know, our sport is a frustrating one so when gymnasts are struggling they may find it difficult to see things clearly. You would be surprised by how much a gymnast will look at you as a source of confidence. When your gymnasts are lacking such confidence and are about to give up, your coaching and reassurance is what will often pull them through and teach them to be resilient.

Summary

Psychological resilience is a key factor that can significantly improve performance. In this blog, we have discussed how you can use mental fortitude training as well as other coaching behaviours to foster resilience in your gymnastics environment. When using mental fortitude training, and more specifically Pressure Inurement Training, it is absolutely crucial to engage in ethical coaching practices and use your knowledge of your athletes to provide the appropriate and safe level of challenge11. It is also worth considering taking a more holistic approach to coaching that may focus on incorporating both emotional and performance intelligence within the gymnastics environment14,15. More importantly, do remember that resilience is not built over night and like most things in life, it takes several different experiences to build character. The sport itself provides a generous amount of opportunities to learn and grow from1 and as long as you are teaching your gymnasts how to cope with these situations and continue to grow stronger, you have done your job as a coach.

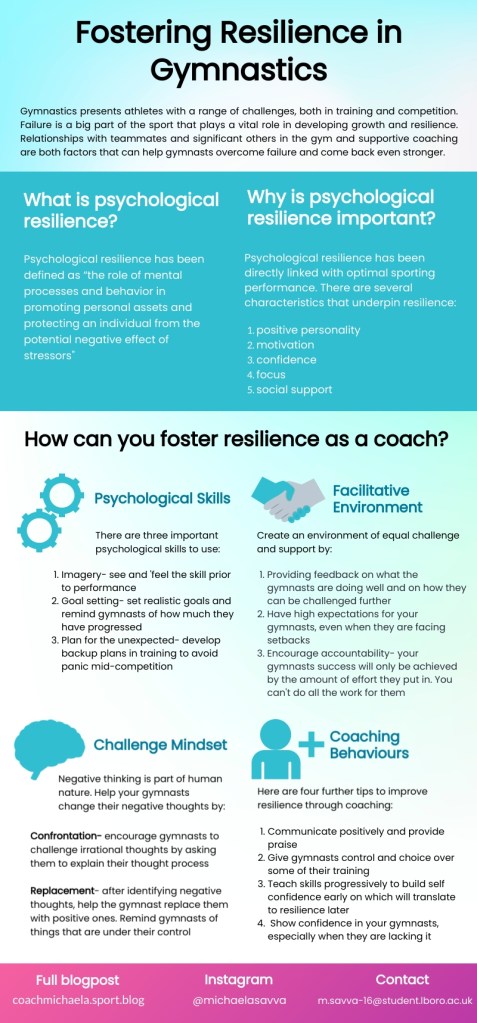

Thank you for taking the time to read my blog. I hope it has been informative and has helped you expand your coaching in a way that both you and your gymnasts can benefit from. Feel free to leave any comments or questions below and check out my infographic that summarises what we have discussed today.

If you have found my content helpful, help spread the knowledge in our community! Thank you and happy coaching!

https://my.visme.co/projects/jw6wyj8q-resilience-gymnastics-infographic

References

[1] White, R. L., & Bennie, A. (2015). Resilience in youth sport: A qualitative investigation of gymnastics coach and athlete perceptions. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(2-3), 379-393.

[2] Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of sport and exercise, 13(5), 669-678.

[3] Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: An evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 7(3), 135-157.

[4] Gould, D., Dieffenbach, K., & Moffett, A. (2002). Psychological characteristics and their development in Olympic champions. Journal of applied sport psychology, 14(3), 172-204.

[5] Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., & Harwood, C. (2012). Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players. Journal of sports sciences, 30(15), 1593-1604.

[6] Hall, C. R., Rodgers, W. M., & Barr, K. A. (1990). The use of imagery by athletes in selected sports. The Sport Psychologist, 4(1), 1-10.

[7] Sanford, N. (1967). Where colleges fail: A study of the student as a person. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

[8] Mahoney, J. W., Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Ntoumanis, N. (2017). Training a coach to be autonomy-supportive: An avenue for nurturing mental toughness. In S. T. Cotterill, G. Breslin, & N.Weston (Eds.), Sport and exercise psychology: Practitioner case studies (pp. 193–213). Chichester, UK:Wiley.

[9] Bell, J. J., Hardy, L., & Beattie, S. (2013). Enhancing mental toughness and performance under pressure in elite young cricketers: A 2-year longitudinal intervention. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2, 281–297.

[10] Oudejans, R. R. D., & Pijpers, J. R. (2009). Training with anxiety has a positive effect on expert perceptual-motor performance under pressure. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 1631–1647.

[11] Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health, 26, 399-419.

[12] Lazarus, R. S. (1964). A laboratory approach to the dynamics of psychological stress. American Psychologist, 19, 400–411.

[13] Lazarus, R. S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

[14] Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Allen, M. S. (2016). Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 26, 862–874.

[15] Jones, G. (2012). The role of superior performance intelligence in sustained success. In S. M. Murphy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology (pp. 62–80). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.